January 14

On 14 January 1981, Jimmy Carter delivered his farewell address to a nation that had recently evicted him from office. Beset by the Iranian hostage crisis, an economy groaning under the weight of deindustrialization, and the revival of Soviet expansionism in Afghanistan, Carter was the fifth consecutive American president to leave office under less than auspicious circumstances. Unlike John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter had survived his term; unlike Richard Nixon, he did not leave office as a disgraced, drunken wreck. But there was little doubt on the night of January 14 that Carter was concluding a failed presidency marked by indecision, divisiveness, and bad sweaters.

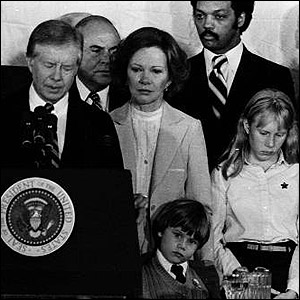

On 14 January 1981, Jimmy Carter delivered his farewell address to a nation that had recently evicted him from office. Beset by the Iranian hostage crisis, an economy groaning under the weight of deindustrialization, and the revival of Soviet expansionism in Afghanistan, Carter was the fifth consecutive American president to leave office under less than auspicious circumstances. Unlike John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter had survived his term; unlike Richard Nixon, he did not leave office as a disgraced, drunken wreck. But there was little doubt on the night of January 14 that Carter was concluding a failed presidency marked by indecision, divisiveness, and bad sweaters.Still, Carter remained upbeat, congratulating the members of his administration for their service and thanking Americans for their kindness and support over the previous four years. Turning from his own departure to the question of national "destiny," Carter reminded his fellow citizens of their obligations to protect universal human rights. As the president explained,

America did not invent human rights. In a very real sense, it's the other way around. Human rights invented America. Ours was the first nation in the history of the world to be founded explicitly on such an idea. Our social and political progress has been based on one fundamental principle: the value and importance of the individual. The fundamental force that unites us is not kinship or place of origin or religious preference. The love of liberty is the common blood that flows in our American veins.Earlier that day, Jimmy Carter authorized the release of $5 million in "non-lethal" aid to the right-wing junta that ruled El Salvador -- funds that doubled four days later, just prior to Carter's exit from Washington, DC. By year's end, Ronald Reagan's administration had announced its commitment to fighting "communism" in Central America. One of its principle aims was to offer unhindered support the Salvadoran government, whose death squads had already begun thinning the population in a civil war that would cost tens of thousands of people their lives by decade's end.

The battle for human rights, at home and abroad, is far from over. We should never be surprised nor discouraged, because the impact of our efforts has had and will always have varied results. Rather, we should take pride that the ideals which gave birth to our Nation still inspire the hopes of oppressed people around the world. We have no cause for self-righteousness or complacency, but we have every reason to persevere, both within our own country and beyond our borders.

***

Eighteen years before James Earl Carter bade the nation farewell, George Corley Wallace announced his triumphant arrival into the Alabama governor's office in Montgomery. In a loathsome ode to herrenvolk democracy, Wallace stoked the fires of white resentment against the modest gains of the civil rights movement, which had entered perhaps its most critical year to date:Today I have stood, where once Jefferson Davis stood, and took an oath to my people. It is very appropriate then that from this Cradle of the Confederacy, this very Heart of the Great Anglo-Saxon Southland, that today we sound the drum for freedom as have our generations of forebears before us done, time and time again through history. Let us rise to the call of freedom-loving blood that is in us and send our answer to the tyranny that clanks its chains upon the South. In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny . . . and I say . . . segregation today . . . segregation tomorrow . . . segregation forever. . . .By the end of 1963, the March on Washington would take place; police officers in Birmingham would unleash German shepherds and fire hoses against unarmed men, women, and children; four young girls would be obliterated in a church bombing in that same city; Medgar Evers would be gunned down outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi; and John Kennedy -- who watched all of this with mounting dismay -- would have his brains scattered across the seats of a limousine in Dallas.

Hear me, Southerners! You sons and daughters who have moved north and west throughout this nation . . . . we call on you from your native soil to join with us in national support and vote . . and we know . . . wherever you are . . away from the hearths of the Southland . . . that you will respond, for though you may live in the fartherest reaches of this vast country . . . . your heart has never left Dixieland.

And you native sons and daughters of old New England's rock-ribbed patriotism . . . and you sturdy natives of the great Mid-West . . and you descendants of the far West flaming spirit of pioneer freedom . . we invite you to come and be with us . . for you are of the Southern spirit . . and the Southern philosophy . . . you are Southerners too and brothers with us in our fight.