January 19

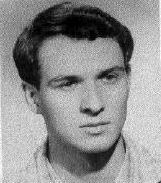

On 16 January 1969, nearly five months after the Soviet Union rolled into Czechoslovakia -- asphyxiating the "Prague Spring," a nonviolent movement to liberalize the country's economy and social order -- a 20-year-old student named Jan Palach doused himself with gasoline on the steps of the National Museum, which looked down over Wenceslas Square in Prague. After lighting himself on fire, he dashed across an intersection and was doused with coal by a transportation worker. Palach suffered third-degree burns over 85 percent of his body and was rushed to a nearby burn clinic at Vinohrady Hospital, where he lived several days before expiring at last on 19 January 1969.

On 16 January 1969, nearly five months after the Soviet Union rolled into Czechoslovakia -- asphyxiating the "Prague Spring," a nonviolent movement to liberalize the country's economy and social order -- a 20-year-old student named Jan Palach doused himself with gasoline on the steps of the National Museum, which looked down over Wenceslas Square in Prague. After lighting himself on fire, he dashed across an intersection and was doused with coal by a transportation worker. Palach suffered third-degree burns over 85 percent of his body and was rushed to a nearby burn clinic at Vinohrady Hospital, where he lived several days before expiring at last on 19 January 1969. Jaroslava Moserova, a doctor who later served in the Czech parliament, attended to Palach during those three days and remembered him in an interview with Radio Prague that was conducted in January 2006, two months before her own death.

Already, as the nurses told me, already when he was in the elevator and being taken up to the intensive care unit, he kept telling the nurses, 'Please try to make them understand. Please tell people why I did it.' When people say that he did it because of the invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies, that's not really so. He did it because of the demoralization that was setting in. He was a young man, he had some hopes in the Dubcek Prague Spring, he had some illusions that it might even work, and he saw, as we all saw, so many people of talent and courage suddenly emerge from nowhere during the Prague Spring. And then so many of these people disclaimed the statements they made during the Prague Spring, so many of them gave in and sold their souls. That was what he couldn't bear, what he wanted to stop. He wanted to do something that couldn't be played down, that couldn't be kept secret, that would necessarily attract public attention, and he really wanted to shake the conscience of the nation.Nearly half a million people observed his funeral procession less than a week later. Using metal truncheons and tear gas, police beat back demonstrators at Wenceslas Statue, where they had gathered to mourn Palach by lighting candles and placing wreaths at the statue's feet. In mid-February another "human torch," 18-year-old Jan Zajic, duplicated Palach's act.

Buried at Olsany cemetary, Palach served as an emblem of Czech resistance and his grave became a popular site of pilgrimage and tribute until 1973, when his body was exhumed and cremated on the orders of the government. An elderly woman was buried in his place. In 1990, after the fall of the communist government of Czechoslovakia, Palach's ashes were returned to Prague and interred once again at Olsany cemetery.